Other Common Style Variations in the Early Phases of Pulling

Lifters vary significantly with respect to certain fundamental aspects of their starting position other than those already mentioned. For example, most lifters begin the pull with the bar over the juncture of the toes and the ball of the foot. However, many athletes place the bar in front of the base of the toes at the start of the pull (though never altogether in front of the toes), and others place the bar over the ball of the foot, behind the toes.

When the bar is placed further away from the body than the base of the metatarsals, it will travel toward the lifter to greater extent during the early stages of the pull than when the bar begins directly over the metatarsals. The distance of this additional movement toward the lifter approximates the added distance between the lifter and the bar at the start of the pull (e.g., if the bar is l“ in front of the base of the metatarsals at the beginning of the pull, the bar will travel an additional inch toward the lifter during the second stage of the pull). Its movement during the later phases of the pull will be similar to the pattern of movement that occurs when the bar starts in a more conventional position.

When the bar is placed behind the base of the toes at the start, it will tend to shift toward the athlete to a lesser extent, by an amount approximately twice the distance that the athlete’s feet are placed forward of the conventional position in the start; e.g., if the base of the metatarsals is 1“ forward of the bar, and the bar would normally have traveled 4“ toward the lifter during the early stages of the pull, it will now travel only 2“ toward the lifter. If the bar is brought still closer to the lifter, it may actually travel away from the lifter during the early stages of the pull. Placing the bar too close to the lifter at the start will also require the lifter to lean back more than is usual during the explosion phase of the pull in order to keep the bar moving in a vertical path. If the placement of the bar is very extreme in terms of placement behind the base of the metatarsals, the bar may actually travel forward at the end of the pull.

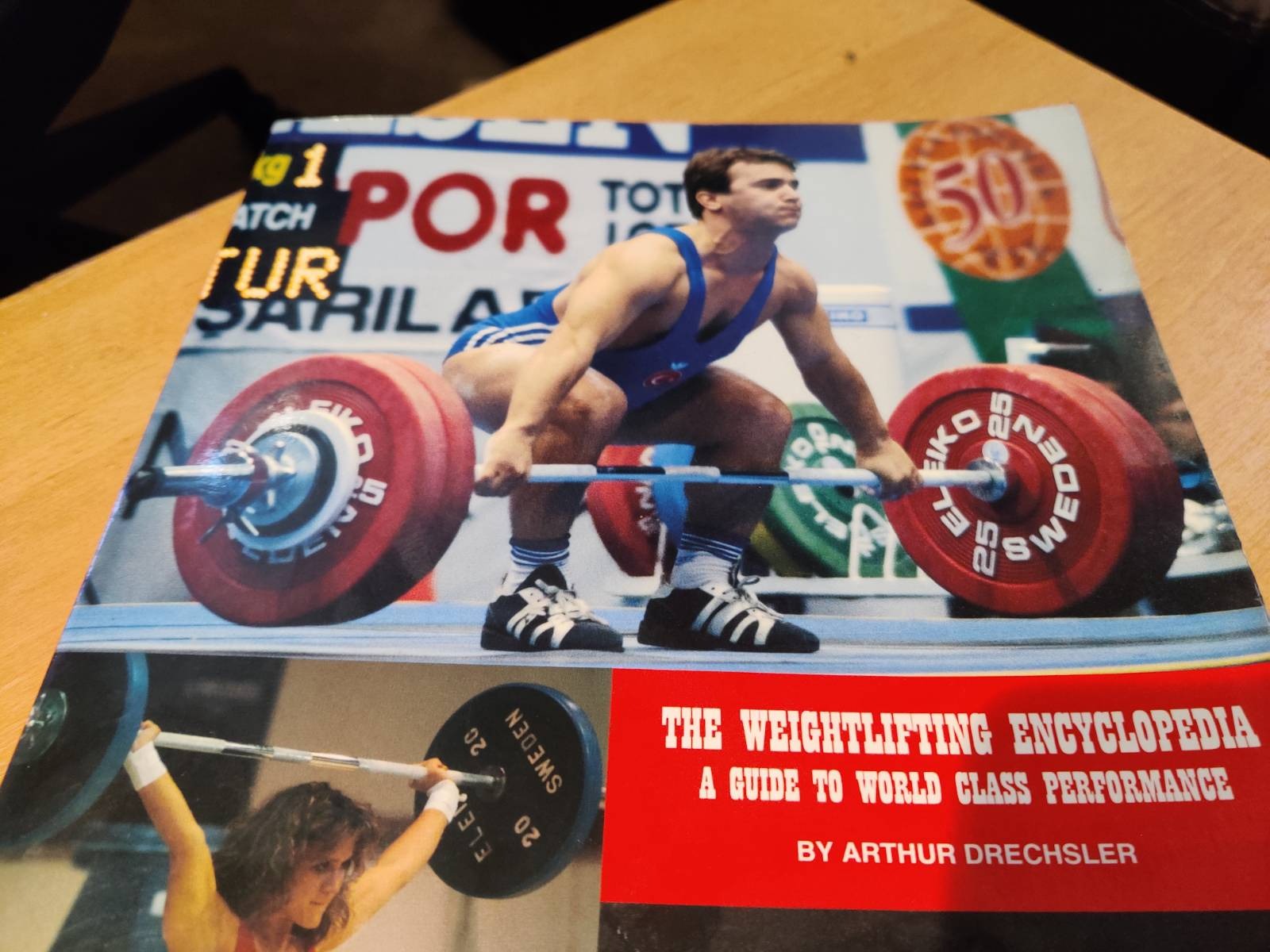

Another common variation in pulling style among lifters involves differences in the angles assumed by the major joints of the body at various phases in the pull. What are the reasons for these differences? The Eastern Europeans often refer to three basic body types in their literature, and they have identified certain technique characteristics which they feel are correlated with those physique types. The mesomorphic type is considered “normal.” An athlete with longer limbs and a shorter torso is generally referred to as the dolichomorphic type. The third type is the brachimorphic, characterized by shorter than average limbs and a longer than average torso.

An example of the kinds of technical differences that exist among lifters with different body types occurs in the starting position. In this position, lifters with shorter legs and longer torsos tend to hold their torsos more upright and to bend the legs more at the start. However, when starting positions vary because of physical characteristics (as compared with technical mistakes), the differences among the positions athletes assume tend to be minimized during the middle stages of the pull (there are differences in the squat position, just as there are in the starting position). Differences that are created by technical errors are not ironed out during the middle stages of the pull. In some cases, the differences grow smaller but in others they grow even larger than they were at the outset.

Naturally, there are an infinite number of variations that extend within and across these fundamental types. All of these major differences in technique and body proportions and many smaller ones can lead to variation in the overall pattern of movement that lifters generate during the lifts.

Some analysts have argued that lifters who are mechanically better suited than the average lifter to use the back in the pull (this could be the result of stronger back and hip muscles, a shorter back or both) will tend to have a greater than normal incline in the torso (i.e., a smaller angle relative to the platform) during much of the pull. As a result, the bar will be lower in relation to the platform than is normal, at least through the second phase of the pull and perhaps later. This results in the lifter being able to exert force over a longer distance in subsequent stages of the pull. However, this is only an advantage if the lifter is not too fatigued to exert force over the entire distance or is not in a mechanical position that lessens the amount of force that can actually be applied, an unlikely set of conditions.

Similarly, some analysts have argued that lifters who have legs that are mechanically better suited than average to lift the bar tend to begin the pull with the torso more upright than normal and to straighten it earlier during the pull than is normal. This results in the height of the bar being greater in relation to the platform than is normal prior to the final acceleration so that the lifter can exert the force during the final acceleration over a shorter distance than is normal. There is also an tendency for the lifter with a more upright torso to straighten the torso faster than the legs during the explosion phase and therefore to generate excessive lean-back at the finish of the pull, with the result that the bar is pulled backward from its starting point on the platform. Roman has suggested that when the bar travels up to 3 cm forward or 5 cm behind the base of the metatarsals after the final explosion has been executed, the bar will end up in an area that is controllable by the athlete. (These distances are guidelines for the athlete of average height; taller athletes have larger tolerances and shorter athletes have smaller ones.) Horizontal movement beyond that point will make it difficult for the athlete to control the bar during the squat under. While this would seem to be a disadvantage. there are some very good lifters who lift in this manner. Therefore, there may be some compensating mechanisms that overcome, at least to some extent, the disadvantage of a shorter distance to accelerate the bar. (For example, since the bar is already higher, it needs to be accelerated less to reach its ultimate height, or the body is in a stronger mechanical position for the shorter explosion than it is for a longer one so that the shorter duration is compensated for by a greater force generation over that shorter distance.)

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to react!