Table of Contents

The Problem

Most nights, I listen to some sort of audio book or play. The joy of being read to sleep is often times spoiled by sudden changes in the perceived volume though, making me either crawl into my speaker in order to understand what’s being said or jump straight up short before I had the chance to fall asleep because the reader’s tone became more exited (and therefore louder). I even tried to limit my selection of content to voice actors I know who can maintain a certain expression over everything they read, but that’s not an option if you want to listen to something specific. To be clear: The issue is not the overall level, that can be compensated for by turning the volume on my device up or down. It’s the ratio between loud and quiet parts, aka the dynamic range. This is like for instance in a piece of classical music, where you sometimes can barely hear the whispering of some flute, where in the next moment all other instruments join in and you are blown off your seat, holding your ears.

What I Tried

Looking for an audio book app that applies some sort of dynamic range compression

on the playback yielded no result (both major platforms included). Apparently, neither does an app exist that does that kind of thing for the general audio output of a mobile device. If I’m wrong, I’m happy to be corrected. Also, I wasn’t and am not willing to pull out a fully fledged computer and mixing setup in my bedroom just so I can listen to audio books at nighttime. Doing the dynamic compression on the fly therefore was out of the question.

On one occasion, I booted up my DAW and pulled in the files in question, applied compressor and limiter to my taste and rendered out the result. While that technically did the job, the process is less than optimal in more than one regard:

- it can’t be done when there’s no DAW available

- you end up with one big file instead of separate ones, which I prefer, as they often have titles and what not, and when searching for the place you left off the night before, this way the progress bar becomes hard to navigate because it has to cover multiple hours of play time instead of minutes

- in order to have single files, you’d need to either work with hundreds of tracks, manually copy-&-pasting the same effect to all of them and then exporting everything as stems, or do some magic with markers and export settings, which is nothing at least I want to do on a regular basis (every time I want to listen to a new audiobook)

What worked

The Central Command

I’ve been long aware that sox exists, but its syntax for dynamic range manipulation kept me from learning how to use it. Only recently though I found out that good old ffmpeg can do the same just as well. I just didn’t know it had the ability for compression & limiting built in, and I quickly found examples online for doing just what I wanted. I tried out some of the relevant filters and until now settled with the somewhat simplistic but effective alimiter. The workflow now revolves around this command:

ffmpeg -i input -filter_complex "alimiter=limit=0.2" output # change 0.2 to taste

The value of 0.2 basically means that everything louder than a fifth of the available dynamic range will have its amplitude squashed down, without any clipping or other audible distortion

, and everything will be amplified as much as possible (“normalized”). That may appeal somewhat harsh, and it in fact does squeeze most of the artistic expression from the voice performance. But since we’re aiming for listenability in a constrained environment here, I found this value to be fitting most cases, and the result is surprisingly little awkward to listen to - and better than the compressor curves I was able to draw with something like - filter_complex "compand=points=-50/-900|-35/-15|-27/-9|-15/-3|0/-6|20/-6:gain=3". There are cases though where this is too much, e.g. when breathing noises become overamplified or the audiobook contains music and/or sound effects that start to sound unnatural. It’s a good idea to test the conversion on a file with all those properties and give it a listen before continuing.

Iterating Over a Lot of Files

The above is all nice and good, but handling a single file is no problem with e.g. Audacity either. We need to process dozens if not hundreds of files automatically. Doing the same repetitive task over and over again is exactly the kind of job computers are good at and people are not.

The obvious Unix tool at hand for a task like this and its usage usually would look something like find -name "*.mp3" -exec ..., but I resorted to its more modern cousin fd. Apart from a more friendly interface, it offers several advantages:

- it’s on its own faster than

find - passed in commands get executed in parallel

- it has nice path parsing built in

To see the latter in action, let’s copy the folder structure of the original audio book (without any files at this point) as a first step. Lots of audio books are divided into CDs or chapters, and we neither want to loose that nor overwrite our existing media files or do the work manually:

# first cd-ing into the directory where our sources are, this cuts the length of the fd line down considerably

fd -e mp3 -x mkdir -p ~/$target/{//}

The really nice thing to note here is the {//} part at the end: It gives us the relative path of the file fd is currently looking at, without having to do regular expression magic or cutting string path representations at the right point ourselves.

Next, let’s do the actual conversion:

# we're still in $source, also replace $target with the folder you want your converted files to go into

fd -e mp3 -x ffmpeg -i {} -filter_complex "alimiter=limit=0.2" ~/$target/{}

If you’ve got more than one CPU core (which should be true unless you’re reading this on a CRT screen), this is where fd’s parallel command execution really shines. ffmpeg is not built to use more than one core, so running this part with find would take as much longer as there are CPUs in your machine.

The last thing you might want to do is to copy additional data like cover images etc

., but in principle, you’re done by now.

Conclusion

TL;DR: Let me sum up the commands for you in one block:

cd $source #assuming this is the directory of the audio book(s)

fd -e mp3 -x mkdir -p ~/$target/{//} # change the extension to what your source material has

fd -e mp3 -x ffmpeg -i {} -filter_complex "alimiter=limit=0.2" ~/$target/{}

The only two things you need for that on your computer are ffmpeg and fd.

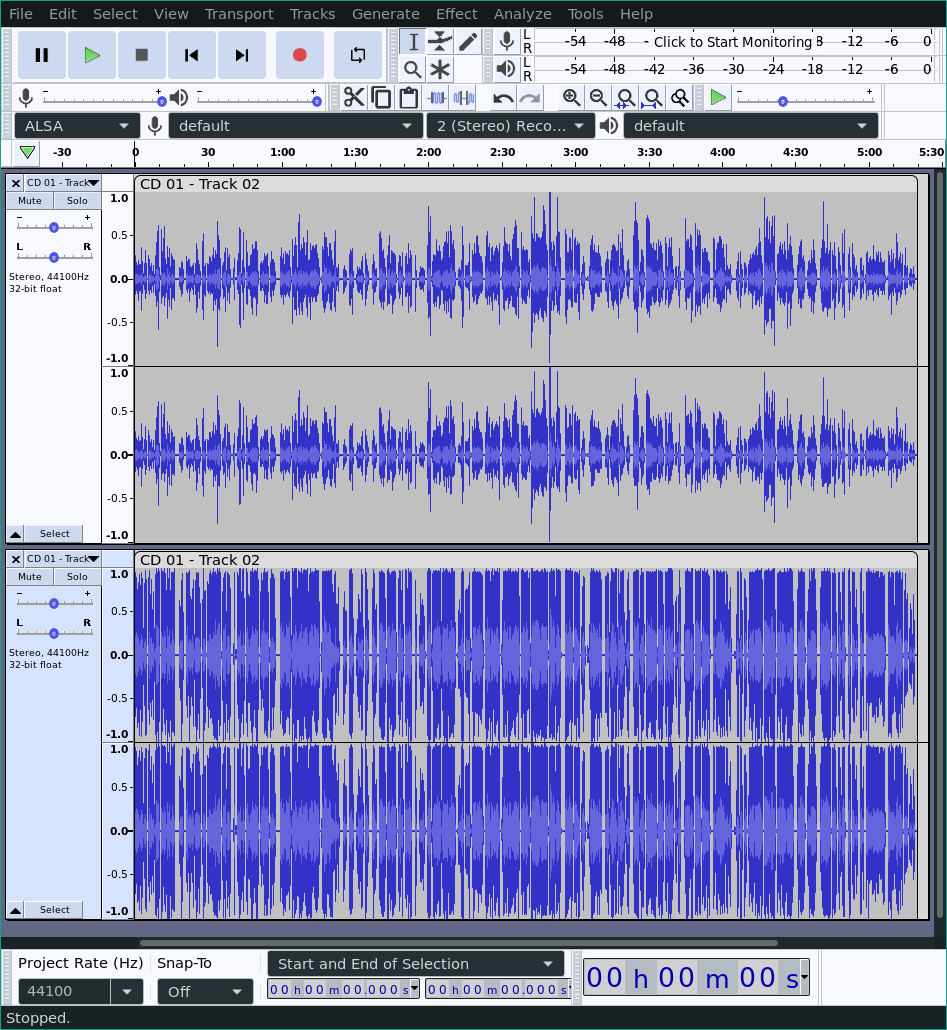

Take a look at the wave form representations before and after our modification. Notice how the ratio between quiet and loud parts has changed:

This can also be advantageous if your hearing isn’t perfect, you’re trying to listen to stuff in an environment with a lot of background noise (e.g. in a crowded train) or your device simply can’t get out enough volume to bring up the quiet parts.

Due to ffmpeg’s flexibility, all the above of course doesn’t only work on mp3 files, but for every sound format our beloved swiss army knife can read (from to top of my head, I couldn’t name a single one it can’t).

This issue has bugged me for years, really! The reason I wrote up this somewhat long-ish piece for what in fact is little more than two lines of shell code is that I’m really glad that I found this solution.

At this point in time, I refrained from wrapping everything into a ready-to-use script, because the differences between use cases are nearly as big as the similarities. If you happen to know though how to execute two commands in one run using fd -x, please let me know. As of now, I haven’t had much luck in using the path placeholders ({}, {//}) in more than one place, e.g. when chaining commands together with &&.

Interaction With This Posting

This is a federeated blog. If you have an account on Mastodon or any other compatible (fediverse) service, you can use it to log in here and comment in the form below.

Footnotes

In this context, the term “compression” has nothing to do with what mp3 does. Dynamic range compression is a concept on its own.

I don’t want to rule out that you can pull that off in a DAW that can be as heavily scripted as e.g. Ardour. Still, I have no idea how to do that. If you do, please let me know!

I’m perfectly aware that any non-linear signal manipulation counts as distortion in the technical sense, I’m using the more colloquial meaning here which can be translated as “unwanted artifacts through digital clipping”

This is something I still do manually, because every audio book is different here

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to react!